Understanding and applying two herbicides to control invasive annual grasses in Wyoming’s geography takes careful consideration and partnership.

Story and photos by Hannah Nikonow, IWJV Communications and Marketing Coordinator

Nancy Webb sees what Wyoming stands to lose if she and others don’t take action now. As the Invasive Annual Grass Coordinator for the BLM’s Wind River and Bighorn Basin Districts, she is mobilizing people to fight a massive land health threat: a non-native plant called cheatgrass. This little weed, unbeknownst to many, is marching into critical sagebrush habitat at an incredible pace and altering landscapes beyond recognition.

Cheatgrass is a tiny, wispy grass. It’s thinner than a toothpick and much more delicate. It is one of many weeds recognized as an invasive annual grass. Although it doesn’t look like much, it delivers a sucker punch to wildlife and livestock, both of which depend on healthy rangelands that provide diverse native vegetation and long intervals between wildfire occurrences.

“I wish more folks understood how fast invasive annual grasses, like cheatgrass, are changing entire landscapes,” said Webb. “They sprout earlier and grow faster than pretty much everything else. Cheatgrass also dries out earlier than native plants. This turns it into fine fuel loads that lead to more wildfires in places that should not be burning so much.”

A Burning Problem

Native plants like sagebrush take decades or more to grow. That slow growth time means that increased fires in sagebrush country can wipe out this keystone plant and the ecosystem it supports. That has major implications for species ranging from mule deer, sage grouse, and pronghorn to livestock and more. People, too, depend on healthy sagebrush rangelands for agricultural livelihoods, recreation, energy development, and more. Increasingly catastrophic wildfire threatens it all.

When sagebrush burns, it burns hot—much hotter than a grass fire. As a result, fires in sagebrush country not only destroy sagebrush but also severely damage the other surrounding native plants. Bunchgrasses, wildflowers, and other native species are the foundation of the sage steppe and the backbone of productive rangelands. These losses have a devastating ripple effect. When habitat-supporting native vegetation disappears, wildlife is forced to navigate a fractured landscape where available nutrition has dropped dramatically. In turn, populations decline. The loss of usable grazing lands for livestock also puts enormous financial and emotional strain on human families and communities.

“This isn’t just a little invasive weed problem,” Webb said. “We can’t sleep on this. Everyone in Wyoming is impacted. We don’t even have a grasp of what the economic consequences are now and what they are going to be in the future.”

Herbicides at Work

There are precious few tools in a land manager’s toolbox to fight this weed. One of the most effective is herbicides. Two specific chemicals have been extensively studied and tested for their ability to control invasive annual grasses without harming surrounding native plants when applied in the right way. Conservation professionals are working to figure out exactly how to use these herbicides in Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin so that they are effective in this dry, high desert.

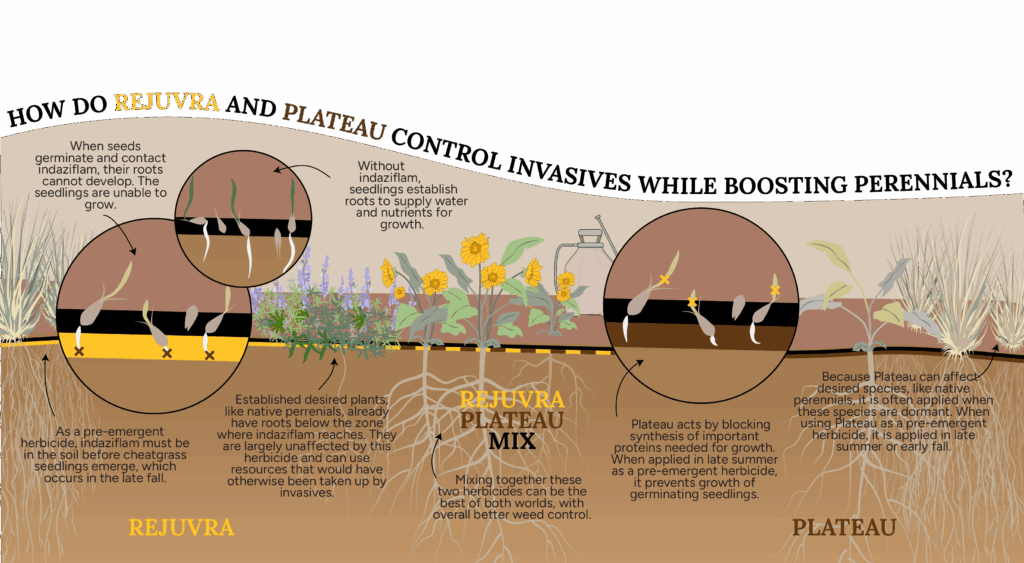

Each herbicide takes a different approach to disrupting invasive grasses. Webb and her partners are using the herbicides Rejuvra (indaziflam) and Plateau (imazapic). Understanding how these herbicides work helps managers like Webb hack annual grass biology.

Rejuvra is a selective, pre-emergent herbicide. That means it targets the roots of invasive annual grass seeds as they sprout and leaves most established plants unharmed. It stays in the top few inches of soil and prevents weed seeds from developing roots. Rejuvra is selective because while it stops new seedlings from trying to grow roots, it generally does not harm mature plants with established root systems, thus protecting native perennial grasses. When applying Rejuvra, it is important to select a site that has recovery potential with existing native plants present, as there won’t be any new seedlings that can grow for up to a few years.

Plateau, conversely, is a pre- and post-emergent herbicide. It inhibits the building blocks of plant cells by entering through the foliage and roots after the plant has sprouted. Plateau affects weeds like invasive annual grasses, but it can also negatively impact desired perennials.

To target cheatgrass as effectively as possible while reducing harm to desired species, technicians like Webb use chemicals like Rejuvra and Plateau in concert, with careful sequence and timing. Rejuvra can be applied at the beginning of the season to work; conversely, Plateau is best applied when plants are dormant, such as in the late summer or early fall. They can also be applied together.

Timing and moisture, whether from rain or snow, are essential to activate these chemicals. Here in Wyoming, managers often have to wait their turn for aerial applicators. This means some treatments don’t happen until later in the summer, which can fall outside Rejuvra’s ideal application window. That said, in the second year after spraying, even with a delayed application, managers often see strong results. The complexity of each herbicide’s differences and requirements means that land managers are making difficult decisions in reaching for Rejuvra, Plateau, or both.

“Ask anyone in land management, we don’t want to spray chemicals across whole landscapes, but it’s our most effective way to control this problem of invasive annual grasses,” Webb said. “We are proceeding very cautiously with these chemicals. They are so extensively tested and deeply studied, and we are considering hundreds of possible factors that could affect what they are going to do in our landscape.”

Build Trust for Future Results

Webb said that since the results of these herbicide applications are most apparent two years after their use, new users can be especially hesitant to try out chemical treatments. This has led Webb and her field technicians to establish a number of demonstration plots to showcase the effects of cheatgrass spraying and build trust in the process. Their demo plots are in easy-to-reach places so they can be used for education and outreach. Anyone can visit and see the results of the different herbicides on cheatgrass and associated native vegetation.

In the fight against invasive annual grasses, land managers often feel like they are losing too much ground, too fast. But Webb and her partners feel otherwise. They are steadily making headway. In her first year, Webb coordinated treatments for invasive annual grass on 20,000 acres of land and led the collection of a vast array of data for vegetation mapping. Now in her second season of field work, she’s well on track to top last year’s accomplishment metrics.

“This will only get worse if we don’t act,” Webb said. “It will only get more costly. But right now we still have a base of good native plants underneath the cheatgrass, and in Wyoming we can get those back. As disheartening as it is, there are restoration options out there—and we are actively working to develop more.”

In cases of annual grass invasions like this one, managers must triage precious investments of time and funding to conserve healthy places and expand from there. Webb and partners recently received additional funding for this work through a grant from the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust. But to her, this is more than just a job of fundraising and prioritizing resources.

“I want my daughter and any kid to understand that the wide-open, beautiful and healthy places they will call home aren’t there by chance, but that there were people who worked really hard to keep them that way,” she said. “Keeping Wyoming liveable for people, for cattle, for wildlife takes hard work, and I’m doing this work now for them later.”

Webb is part of the Sage Capacity Team, which includes dozens of field-based range specialists, biologists, and other conservation professionals. This team is supported by an intra-agency agreement between the Intermountain West Joint Venture and the Bureau of Land Management, as well as many local and regional partners. Learn more about this team here. Webb’s role is housed in the Wind River/Bighorn Basin BLM field office and hosted by the University of Wyoming’s IMAGINE program. Her position is also supported with funding from the BLM, ConocoPhillips, and private donors. To learn more about invasive grass management in Wyoming, click here.