Collaboration Enhances Bear River Watershed Conservation Easements

“We recognize who we are in Utah and what we have, and we want to protect it. Everyone can agree that this work is important.”

– Jim Bowcutt, Director of Conservation, Utah Department of Agriculture and Food

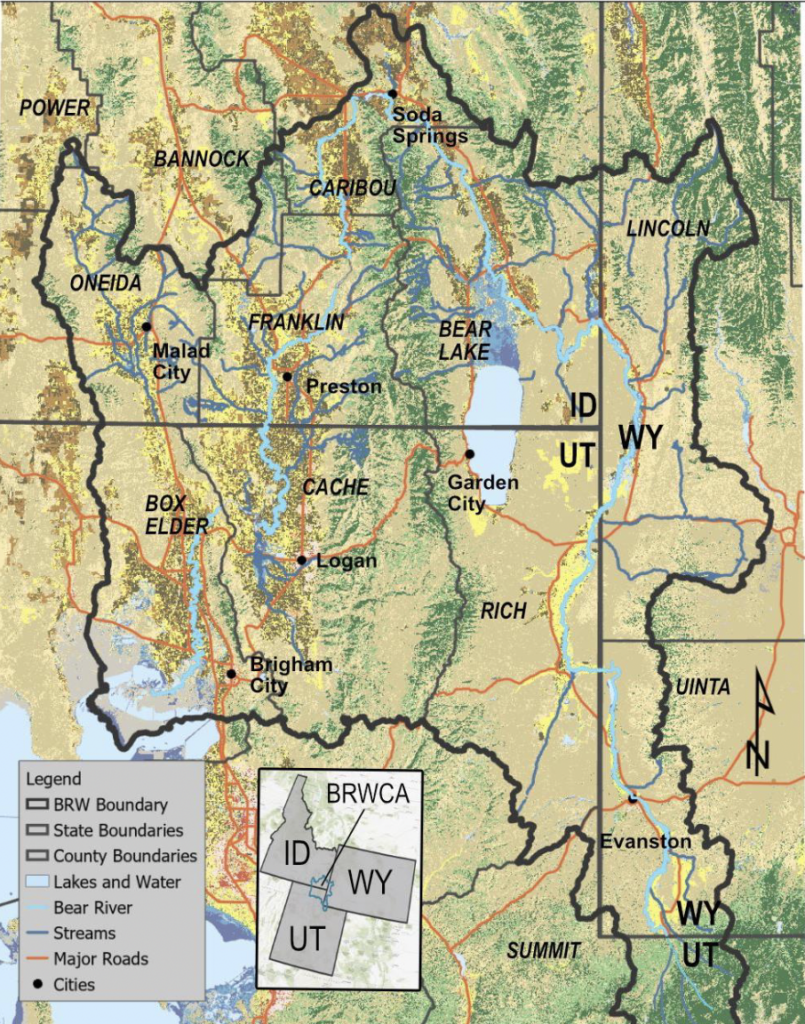

As the urban sprawl of the Wasatch Front creeps further up the Bear River, spilling out of Utah and into Idaho and Wyoming, houses and developments compete with wildlife habitat, agricultural land, and open space. This kind of land rush—one that is playing out in landscapes across the West—challenges landowners to balance the value of their land and way of life versus what a hefty check from a developer could bring them. In that balance hangs the health of the Bear River, the water it carries to the Great Salt Lake, and the habitat it provides for migratory birds, fish, and other wildlife.

In the Bear River Watershed, conservation easements are an increasingly available option for landowners who seek an alternative to development. Erin Holmes, the Project Leader at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS) Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge, said that the threat of development has made conservation easements a more sought-after tool for the watershed’s landowners and conservationists alike.

“Landowners generally want to see their property protected and they want to see the array of life their land supports protected,” Holmes said. “They’re just trying to keep what many of them have had for generations going.”

“To get to this level where we are finding these win-wins, everybody really has to communicate their interests and issues well, and listen to others’ interests and issues. The Environmental Coordination Committee provides a space for that. People come in and are genuinely interested in working with everyone else. That yields better levels of trust, better project delivery, and enhanced collaboration. It starts when people come to the table and are frank about their interests when it comes to talking about projects.”

–Mark Stenberg, Senior Project Manager, PacifiCorp

Conservation easements have faced many hurdles in landscapes across the West, not the least of which is the collaboration and coordination it takes to make it possible for an interested landowner to place land under an easement that aligns with their goals. In the Bear River Watershed, increased land trust capacity and a high level of collaboration between state, federal, and non-governmental organizations mean there are now a number of routes to securing a private land easement, depending on the values a landowner is trying to conserve. People who want to sustain the open space their land provides might work with one of a few land trusts in the area. If they know their land provides important wildlife habitat, they might work with the USFWS through its Bear River Watershed Conservation Area project.

In 2013, the USFWS approved the Bear River Watershed Conservation Area project aimed at working with private landowners to establish voluntary conservation easements throughout the Bear River Watershed. The diverse landscapes within the Conservation Area support migratory birds within the Central and Pacific Flyways, as well as migratory linkages for many mammals, such as elk and pronghorn. A number of native fish species, like Bonneville cutthroat trout, are supported by rivers and lakes within the watershed.

Meanwhile, farmers and ranchers who want to ensure that their land stays in agriculture, can work with partners like non-governmental organizations, state and local agencies, or Native nations to apply for one of USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) programs. Scott Morton, the Assistant State Conservationist-Easement for NRCS Utah, said that easements are frequently sought by producers looking for a way to make their operations more sustainable—or attainable for future use—in the face of urbanization.

“A lot of farmers want to protect land that their family has worked very hard on for generations, farmers can enter their land into a conservation easement to help keep it in place for future generations to enjoy and work on,” Morton said. “Entering into a conservation easement can sometimes help offset the costs of high land prices for young or socially disadvantaged farmers.”

“The NRCS might be working to try to keep land intact for agricultural use, but the resulting conservation easement can coincide with missions of other groups such as keeping land as open space, maintaining certain wildlife habitat, and keeping the water resource available in the future.”

–Scott Morton, Assistant State Conservationist–Easement, USDA NRCS Utah

Even if a landowner is simply trying to restore habitat function on their land, an easement might be a useful initial or follow-up tool to accompany the work. Jim DeRito, the Fisheries Restoration Coordinator for Trout Unlimited’s Western Water & Habitat Program, works throughout the Bear River’s tri-state watershed and said that restoration work along the river, the kind Trout Unlimited specializes in, is becoming increasingly dependent on protecting private land from development through conservation easements.

“There’s a huge need for easements and a huge demand for it; we just haven’t had the capacity in the past,” DeRito said.

There’s a mountain of behind-the-scenes work that goes into creating a conservation easement, from working with an interested landowner to finding funding. Although the capacity to make it all happen is still a dire need among all partners in the Bear River Watershed, the issue was partly alleviated in 2021, when Matt Coombs became the Bear River Watershed Conservation Coordinator.

“Our conservation easement will be in perpetuity. That’s good for what we’re doing at Wuda Ogwa because the wetlands we are going to restore won’t be changed and the new river channels won’t be disturbed. Everything we’re doing to protect the water and the area won’t ever be affected by someone coming in and trying to develop the land.”

–Brad Parry, Tribal Council Vice Chairman of Natural Resources, Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation

Coombs’ position works between Utah’s Bear River Land Conservancy and Idaho’s Sagebrush Steppe Land Trust to accelerate the pace of conservation easements in the watershed. A big part of his work is building relationships across Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming—both with landowners, government agencies, and organizations like Trout Unlimited—to coordinate conservation efforts all along the Bear River. Coombs said it’s more strategic to approach easements this way because conservation on private lands is more likely to occur when a landowner has a menu of options for conservation.

Matt Coombs, the Bear River Conservation Coordinator, poses for a portrait on an easement he helped close. Early investments from the Intermountain West Joint Venture Management Board were critical in creating the Bear River Conservation Coordinator position and have allowed this position to grow and sustain longer-term funding. The success of the position is evidence that early investments in capacity are essential for building relationships, leveraging partner dollars into multiple sources of sustained funding, and thus scaling up and increasing the pace of conservation in important landscapes like the Bear River Watershed.

Matt Coombs, the Bear River Conservation Coordinator, poses for a portrait on an easement he helped close. Early investments from the Intermountain West Joint Venture Management Board were critical in creating the Bear River Conservation Coordinator position and have allowed this position to grow and sustain longer-term funding. The success of the position is evidence that early investments in capacity are essential for building relationships, leveraging partner dollars into multiple sources of sustained funding, and thus scaling up and increasing the pace of conservation in important landscapes like the Bear River Watershed.

“We’re trying to find an option that fits the needs of the property and the goals of the landowner,” he said. “In some areas, the best option might be an easement with [the Bear River Land Conservancy or the Sagebrush Steppe Land Trust], in others, it might be an easement with the USFWS, other places might just need funding to do restoration work.”

“We’re blessed with a lot of flood irrigation in the Bear River Valley, which is really important for the migratory birds that nest around the refuge and use it as stopover habitat during their migrations. Easements allow farmers and ranchers to continue their current practices. In the long run that prevents development; it also keeps the water tied to the land and continues those benefits for migratory birds.”

–Jeremy Jirak, Refuge Manager, USFWS Bear Lake National Wildlife Refuge

Wuda Ogwa (Bear River) is the site of the Bear River Massacre, the single largest mass killing of Native Americans in U.S. history. The site is stewarded by the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation and is undergoing restoration work to enhance the cultural and habitat values provided by the riverfront site. A Cultural and Interpretive Center is planned for the site, and will educate visitors about the history and culture of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation.

The Environmental Coordination Committee (ECC) was established in 2002 to guide work carried out under a Settlement Agreement concerning PacifiCorp’s Bear River Hydroelectric Projects in Idaho. This stakeholder group seeks to employ an ecosystem restoration approach to accomplish resource restoration and enhancement in conjunction with hydropower operations, recreation uses, and other beneficial uses of the Bear River. Grants awarded by the ECC’s Land and Water Conservation Fund contributed to the protection of 3,835 acres and 15 miles of riparian protection along the Bear River and its tributaries in Idaho.

Brad Parry, the Tribal Council Vice Chairman of Natural Resources for the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, said conservation projects like the Tribe’s wetland and riparian restoration work at Wuda Ogwa (which will be complemented by a Sagebrush Steppe Land Trust-held easement), are enhanced and enabled by this mindset. He said the tools each partner brings to the table, from restoration expertise to conservation easement acquisition to the wisdom and guidance provided by the Northwestern Band of Shoshone Nation’s Tribal Council, are all important in protecting areas like Wuda Ogwa in perpetuity.

“The Tribe could never do this on our own,” Parry said. “We’re a small tribe, and having partners is critical to making sure we have what we need to get this work done.”

“Protecting something is a lot easier and a lot less costly than going in and restoring it. If you can buy the development rights and keep people from building in the floodplain, it’s better for the rivers and it’s better for the fish.”

–Jim DeRito, Fisheries Restoration Coordinator, Western Water & Habitat Program, Trout Unlimited

The multiple jurisdictional boundaries crisscrossing the watershed, as well as forums like PacifiCorp’s Environmental Coordination Committee, have created a foundation for dialogue between state and federal agencies, tribes, and nongovernmental organizations. Gabe Murray, the Operations Manager for the Bear River Land Conservancy, said that there is a high level of communication and coordination among conservation entities, avoiding a “too many cooks in the kitchen” scenario.

The result is a partnership network that makes conservation in the watershed a much more collaborative affair. Sara Saunders, the NRCS Utah Field Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) Program Manager, said that RCPP funding secured by Bear River partners in 2022 is evidence of this collaboration’s effectiveness.

“In a watershed that is so important to the Great Salt Lake as well as all three states, having all these partners that know different areas of the watershed and have different areas of expertise makes conservation more powerful,” Saunders said.

And that watershed-scale conservation, said Murray, is something that all of the partners in the watershed can get behind.

“The future of conservation in this area is not going to be buying more federal land, it’s going to be working with private landowners. That’s why conservation easements are so important.”

–Erin Holmes, Project Leader, USFWS Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge

“We have a shared vision for what we’re trying to accomplish here,” he said. “When we can act on that, conservation easements can be easier for the landowner and more strategic in upholding the conservation values we all care about.”

As conservation easements become more attainable for landowners in the Bear River Watershed, these partnerships are a reminder that good people doing good work—collaboratively—is a sure sign of a more resilient future.