Conifer Removal

Targeted Conifer Removal Improves Sagebrush Habitat

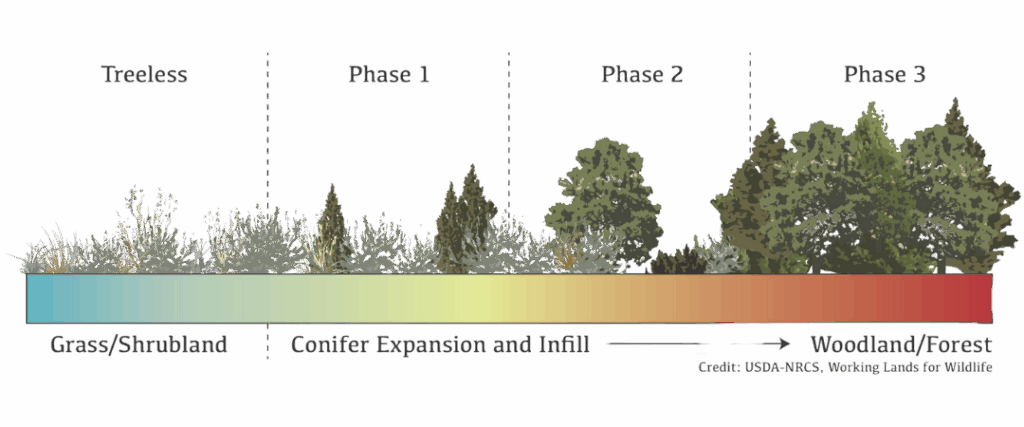

Across the sagebrush sea, pinyon and juniper species are expanding into historical shrubland and grassland systems.

This creates a management challenge for these ecosystems, as expanding trees threaten habitat for sage grouse and other wildlife species.

This expansion also alters ecosystem function by competing for water and other resources, displaces native shrubs and grasses and decreases landscape resiliency to climatic changes. In a collaborative effort, land managers across the sagebrush biome use targeted conifer removal to improve and maintain habitat for sage grouse and other wildlife, increase rangeland productivity, and restore the quality of working sagebrush landscapes across public and private lands.

Since 1860, cover of pinyon and juniper species has increased by 125-625%. Increases in cover are explained by trees expanding their footprint into formerly treeless areas, like sagebrush steppe and grasslands, and infill of existing pinyon-juniper woodlands. About 80% of increased cover occurs as infill within existing woodlands. Both infill and expansion are thought to be a result of changing climate, historical management, and fire suppression, although research on this topic is not conclusive, and these causes vary spatially across the sagebrush biome. Local data is needed to identify trends, drivers, and appropriate management approaches.

Despite their paramount importance, many springs, streamside riparian areas, and upland ephemeral wet meadows are degraded by headcutting, gully erosion, channel incision, vegetation loss, and other forms of degradation. These impacts disconnect wet areas from their floodplains, reducing natural resilience to drought and water storage capacity. Sustaining these scarce water resources is critical to proactively conserving the sagebrush ecosystem and working lands in the West, and will help to contribute to drought resilience as climate changes.

As trees expand into the sagebrush, they reduce perennial grass, forb, and shrub cover. These changes can reduce habitat and forage for wildlife and livestock, and increase the risk of high severity fires. Sage grouse move out when trees move in, actively avoiding areas with more than 4% conifer cover. However, recent research in the Warner Mountains of Oregon showed that where junipers were removed, the sage grouse population growth rates were 12% greater than where no trees were cut. Land managers use this growing body of research to design treatments that help improve habitat for sage grouse and other sagebrush-dependent wildlife.

Our woodland management work within our Partnering to Conserve Sagebrush Rangelands partnership primarily focuses on conifer expansion as a sagebrush management challenge. Learn more about the IWJV’s work to conserve and restore persistent pinyon-juniper woodlands under our Western Forests Program.

putting science into practice

A growing body of science and tools are available to help managers target conifer removal treatments to improve and maintain wildlife habitat and achieve other management goals. We support our partners in using these tools and implementing targeted conifer removal efforts. Learn more about what we’re up to:

Here’s what we’re working on:

Implementing strategic conifer removal for sage grouse

Members of our Sage Capacity Team support strategic conifer removal efforts across the sagebrush biome. As of 2022, our partnership has already completed conifer removal on 300,000 acres across the sagebrush biome. Reach out to Charlie Holz, our Sagebrush Field Delivery Capacity Specialist, to learn more.

Supporting the integration of spatial and monitoring data into conifer removal project prioritization and planning

Our Science to Implementation Team supports our partners in using the latest data to prioritize and plan conifer removal work, maximizing ecological and wildlife benefits. Reach out to Andrew Olsen, our Science to Implementation Coordinator, to learn how we can support you.

SUPPORTING SCIENCE & RESOURCES

Conifer Encroachment Education Project

The Conifer Encroachment Education project website provides information on simple approaches to addressing conifer encroachment into core sagebrush habitats.

Resilient Landscapes Resource List

The latest science and tools for conservation in the Intermountain West.

Partnership in Action

Southwest Montana: A Geography of Sagebrush and Hope

A spotlight of the work of the Southwest Montana Sagebrush Conservation Partnership.

Horizon to Horizon: Improving Habitat at a Landscape Scale

Mapping Change Across Idaho’s Bruneau-Owyhee Sage-grouse Habitat Project.

Conifer Removal Restores Human and Wildlife Community Health

Conifer removal success in east-central Nevada.