Active Management

Active management is one approach to reducing hazardous fuels to prevent catastrophic high-intensity fires and improve wildlife habitat.

MANAGING TOWARDS RESILIENCE

As people and ecosystems confront larger and more severe wildfires, active management can address this wildfire crisis by returning natural fire regimes to forested systems. The main approaches used–thinning, prescribed fire, and a combination of the two–have been shown by science to change the behavior of wildfires that encounter them, increasing resilience to fire. Additionally, they can increase habitat for wildlife that prefer open forests.

LEVERAGING KNOWLEDGE FOR MANAGEMENT

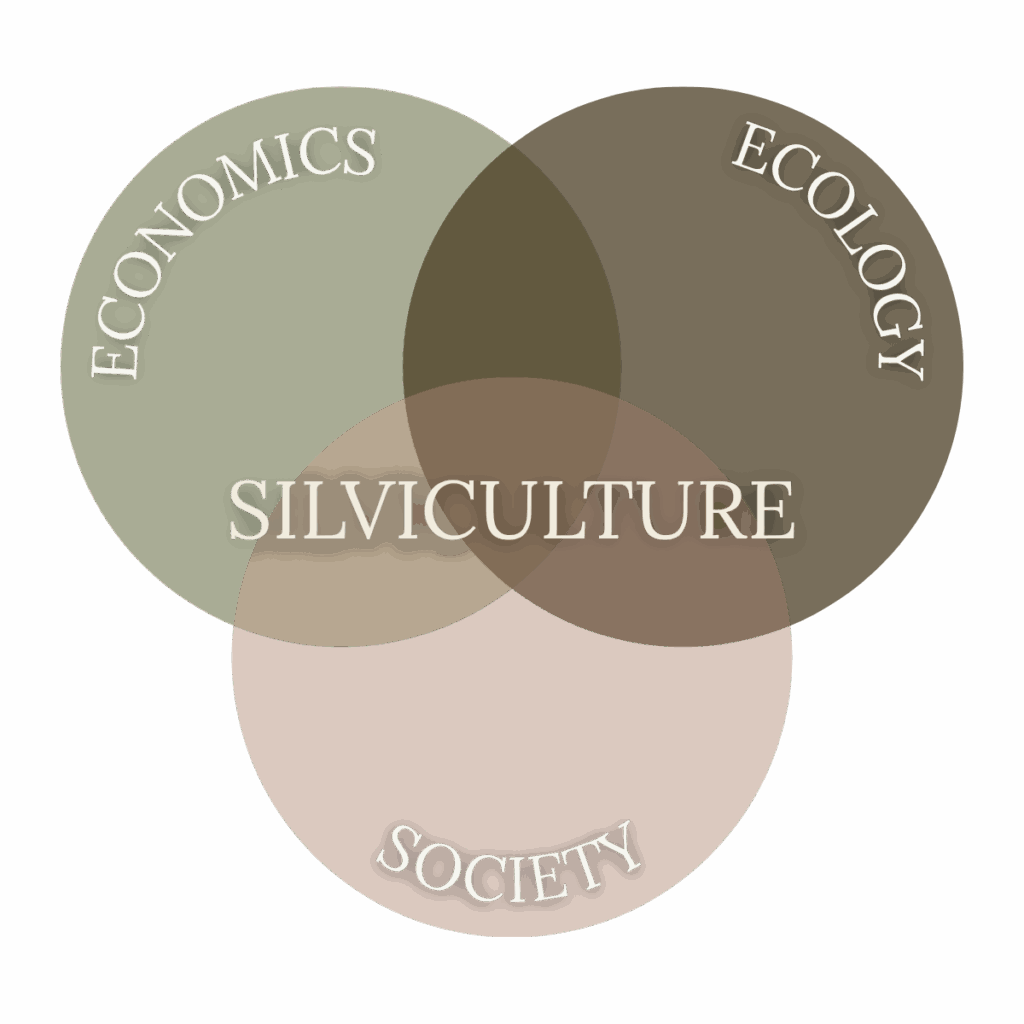

Forests have been managed for as long as humans have lived with them, guided by Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Indigenous Science, and, more recently, silviculture. Silviculture developed in Europe starting in the 16th century to sustain forests and the benefits people receive from them.

KEY TERMS

Silviculture

The art and science of supporting and stewarding forest and woodland ecosystems to foster the diverse values that forests contribute to people and society.

Stand

A contiguous group of trees sufficiently uniform in age, composition, structure, and site conditions to be a distinguishable unit.

Structure

The three-dimensional arrangement of trees and other plants, in combination with nonliving spatial elements such as soils, slopes, and hydrology.

Composition

The unique combination of plant species, including overstory trees, shrubs, and understory grasses and forbs, at a given spatial scale.

Yield

The quantity of forest products, such as timber, from a given area over a given period.

Today, silviculture represents the application of ecology to forest management. It focuses on multi-value management that enhances wildlife habitat, clean water, and other vital elements of ecosystem health and function.

Silvicultural practices can change a forest stand’s structure, composition, growth, and yield. At a stand or landscape level, forest management activities are based on a silvicultural prescription, or a series of management activities over time, meant to move that forest toward a desired future condition.

CREATING A MOSAIC FOR WILDLIFE

A common goal of active management is creating habitat heterogeneity, or patchiness. With fire suppression, forests have become more dense and uniform. Creating patches with different habitat types is beneficial for wildlife: open treeless or low-density areas, old growth with large trees, burned areas with snags, denser riparian or mesic areas, aspen stands, and the edges between the patches. For birds, researchers have shown that forest treatments can create habitat for species that like open forests, while maintaining habitat for closed-forest species. Wildlife like deer and elk can benefit because high-quality forage increases after treatment. Indigenous Peoples have been burning to promote wildlife forage and harvest for millennia.

Photo credit: Mick Thompson.

Photo credit: Christian Collins.

Photo credit: Tom Benson.

ACTIVE MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Thinning

Thinning uses mechanical harvesting techniques to reduce tree density, providing more light, water, and nutrients to remaining trees. Additionally, thinning separates tree crowns, making it less likely that a fire will climb from the forest floor and spread from tree to tree in a high-mortality crown fire. In many cases, thinning also targets the removal of shorter trees, “ladder fuels, ” which can be a bridge from a surface fire to the canopy.

PRESCRIBED FIRE

Anthropogenic fire, including traditional burning and prescribed fire, uses planned fire to meet management objectives. These approaches reduce fuels in the understory by burning small trees, shrubs, and other understory species, and dead material on the ground. Frequent burning benefits native grasses, which may be desirable for wildlife or livestock. Note that this practice is not appropriate in ecosystems that did not historically experience frequent fire.

THINNING & PRESCRIBED FIRE

The magic really happens when thinning and prescribed fire are used together. The most effective way to reduce hazardous fuels and prevent catastrophic high-intensity fire is to apply thinning and then put fire on the ground. Thinning is implemented first to prepare stands for low-intensity fire, allowing burns to replicate historical fire conditions. Then, woody debris created by the thinning and existing understory fuels are burned in a “broadcast” prescribed burn.

SEE THE EFFECTS ON THE GROUND

Aerial view shows the differences in tree mortality after the Bootleg Fire resulting from different types of forest restoration. Photo credit: Steve Rondeau, Klamath Tribes Natural Resources Department, via the Nature Conservancy.

The effects of thinning, burning, and thinning + burning treatments before, during, and after wildfire. From Davis et al. (2024).