Dry, Frequent-Fire Forests

Frequent low-intensity fire shaped the dry forest communities of the Intermountain West. A century of fire suppression has dramatically altered the landscape.

THE IMPORTANCE OF Indigenous Burning

Historically, frequent fires resulted from summer lightning and cultural burning by Indigenous Peoples. Until colonization, Indigenous Peoples burned in spring and fall for a variety of reasons, including perpetuating culturally important plants such as camas (Camassia quamash) and huckleberries (Vaccinium spp). Burning by Indigenous Peoples was prohibited under colonization. Returning this practice to the landscape is ecologically critical and necessary to support Indigenous sovereignty.

Camas blooming in Packer Meadows, where Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) people have harvested Camas for countless generations. Photo Credit: Joni Packard.

FORESTS BUILT FOR FIRE

Many forests of the Interior West are dominated by sun-loving, drought-tolerant, wildfire-loving trees. Historically, fire occurred frequently, from every 4-6 years in the Southwest to every 20-30 years in the northern Rockies. The short return interval of these fires prevented fuels from building up, keeping the severity of most fires low. They favored fire-resistant species like Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and limited more shade-tolerant species such as Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). Frequent fire promoted understory grasses rather than woody shrubs. These conditions created open, park-like stands, reinforcing the frequent low-intensity fire behavior.

Creating a Mosaic ACROSS THE LANDSCAPE

Over millennia, this pattern of frequent, low-intensity fires on dry sites created a patchwork pattern on the landscape. The Intermountain West was a mosaic of grasslands, open forests, and denser, wetter forests found on deeper soils, north slopes, and at higher elevations. Now, forests are more dense and uniform, reducing habitat for wildlife that prefer variety: open spaces, edges, burned areas of different ages, older forests, or the patchiness of mixed ages and densities.

A FEAR OF FIRE DOMINATES

The natural pattern of frequent fires in many ecosystems was interrupted starting in the 19th century by the westward expansion of settlers. Cultural burning was not understood and was often outlawed. The new worldview, where fire was seen as an enemy threatening natural resources used by humans, led to the active suppression of wildfire. This paradigm continues to the present day. As a result, today’s fires are larger and more severe than the fires of the past, threatening ecological integrity and human communities.

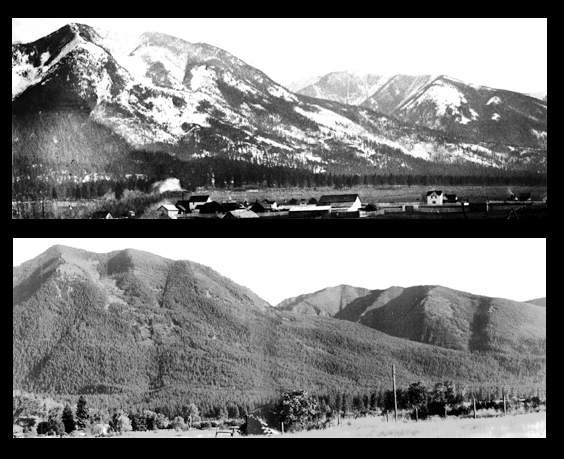

Historically, in the homelands of the Salish and Kootenai people, forests were less dense and more patchy than they are currently (top photo: ~ 1920, bottom photo: ~100 years later). Photo credit: CSKT Division of Fish, Wildlife, Recreation, & Conservation.

BRINGING BACK FIRE

Today, despite recognition of fire’s role, human development and infrastructure, along with the changes that have occurred to forests due to fire suppression, limit natural fire regimes from occurring. As large and severe fires increase, many groups are working to return to historical fire regimes. Across the Intermountain West, collaboration to return low-severity fire to the landscape is growing. Often led by Tribes, multi-stakeholder partnerships, or federal and state agencies, these efforts aim to remove fuels built up by years of fire suppression and return low-severity fire to the landscape. Guided by Indigenous and Western science, these efforts are seeing success when wildfires return, changing fire behavior and ecological outcomes.

An overly dense forest, a result of fire exclusion, in northern New Mexico. The 2-3-2 Cohesive Strategy Partnership is working together to reestablish natural fire regimes in this area.

William Foster with the New Mexico Energy, Minerals, and Natural Resources Department, Cody Dems with the Forest Stewards Guild, and Andrea Jones with the U.S. Forest Service work together as part of the 2-3-2 Cohesive Strategy Partnership.