Strategic Funding Pools allow NRCS to provide locally focused conservation that benefits producers and wildlife.

Standing in a couple of inches of water down in the floodplain of the Bear River, Ben Weston surveyed one of his hay fields. Tall green grasses reach up to his waist, bowing in the gusts created by a hot afternoon wind. Although Weston shut off his ditches days ago, toads splash about in the still-full ditches, serving as a reminder that the irrigating isn’t done yet. The wet hems of his jeans are another indicator that, down at the ground level, the water is taking its time to saturate the soil.

As Weston walked by, a pair of sandhill cranes erupted out of the grass into a blue July sky. He looked out at the river on the other side of his field, hidden from sight by the height of the grass and a line of willows. Being right up against the banks of the river is picturesque, especially with the rise of the Crawford Mountains framing the eastern horizon. It also means that Weston, who ranches cattle and sheep in Utah’s Rich County and gets water from a diversion upstream of these hay fields, is the last stop on the ditch before water returns to the river. That, along with culverts that need to be replaced, can be prohibitive when it comes to trying to produce enough hay to feed his livestock.

“In low water years, some of the water never even gets to me,” Weston said. “Last year, which should have been the best year with the winter and the amount of snow we got, I bought 4 or 500 tons of hay [because of a culvert failure on a ditch]—that’s a lot of money. If I can make my irrigation more productive and more consistent, maybe I won’t have to buy so much hay.”

That’s one of the reasons he said he jumped at the opportunity to apply for funding for a measuring device and new culverts through a Strategic Funding Pool (SFP) from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in Utah. The SFP for Flood Irrigation Infrastructure and Wildlife Habitat Improvement is meant for flood irrigators like Weston, who are facing increasing difficulties managing irrigation water due to aging infrastructure like culverts and levees. The SFP prioritized funding for Rich County producers to help update their flood irrigation infrastructure in an area where widespread flood-irrigated grass hay practices provide important wetland and wet meadow habitat for wildlife.

The Bear River winds through sagebrush hills, leaving a ribbon of verdant hayfields and riparian vegetation in its wake. That green ribbon not only provides habitat for migratory birds (Cokeville Meadows National Wildlife Refuge is just a few miles north of Rich County), it also gives upland wildlife like mule deer and antelope critical access to water and forage. Recent research shows that spring irrigation flooding on pastures like Weston’s creates habitat for migrating and breeding sandhill cranes.

The river also is a source of irrigation water for ranchers like Weston. Being at the top of the Bear River watershed means the water that Weston puts on his field directly impacts the water received by users downstream—all the way to the river’s terminus at the Great Salt Lake. The SFP is an acknowledgment of the role that flood irrigation can play in both providing wildlife habitat and influencing return flows to the river, while maximizing the efficiency of the practice. A 2024 study published in Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment used satellite imagery to identify that flood-irrigated grass hay, like Weston’s field, provides 58 percent of temporary wetlands (shallow wetlands that exist for fewer than two months each year) and 20 percent of seasonal wetlands (wetlands that remain wet between two and six months each year) important to migratory birds.

Aging infrastructure can make it difficult for producers who flood irrigate to continue providing those benefits. Simple modernization tools, from new headgates or even water measuring devices, can make a huge difference in the amount of water used by flood irrigators. Jessica Anderson, a Rangeland Conservationist for the NRCS who took the lead on the SFP program, said that a huge barrier for Rich County irrigators like Weston is that it’s hard to tell how much water they are applying.

“Our biggest problem here is measuring devices,” she said. “When it’s not measured, people don’t know how much to take.”

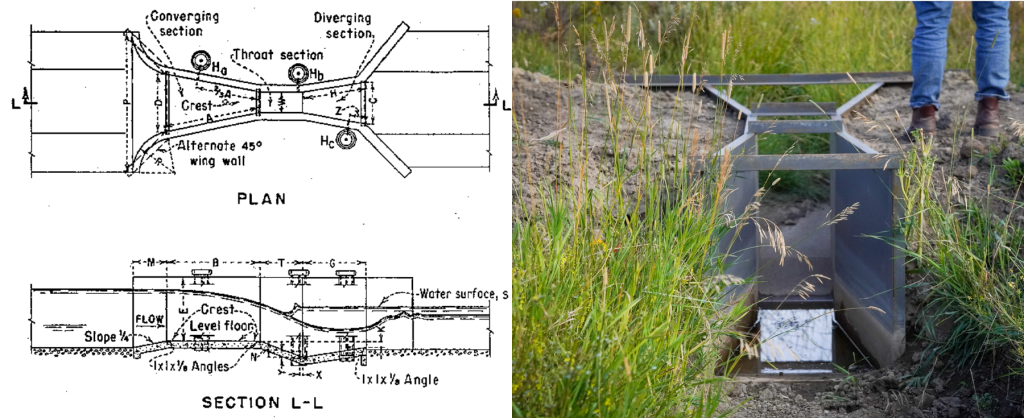

Water measuring devices like flumes, shown above, can help irrigators monitor how much water is flowing through their ditches. Additionally, replacing old culverts with newer, wider-dimensioned models (below) can help get irrigation water get to where it needs to go.

Weston agreed; installing the measuring device just above his river-adjacent field should help him understand his water use better. Another phase of his project will help him replace seven different culverts that are either too old or too small to deliver water at a rate that helps him irrigate the entire field. At one point, he said he considered just scrapping flood irrigation altogether and converting his irrigation system to a center-pivot sprinkler, but he ultimately decided that would be worse for the watershed that he irrigates in. After irrigating the grass, the leftover water returns through the ground into the adjacent river.

“If you start changing some of this flood irrigation to pivot, it can be great for efficiency but then you’re going to mess up things down below it,” he said. “This whole system is built to recharge down below. If I put pivots in this field, that’s 32 cubic feet per second that doesn’t go back into the river and that would affect how everyone else who uses the river can irrigate.”

Having an SFP dedicated to flood irrigation infrastructure is important for keeping that water in the system. Without it, Anderson said, it can be difficult for flood irrigation infrastructure like culverts to rank high enough to receive funding through other programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program because, depending on the year, those programs can prioritize conversion to sprinkler systems.

“If you have a resource concern in a certain area, an SFP will help you get a lot of work done in a shorter period of time,” Anderson said. “You can get a lot of conservation on the ground because [the projects don’t have to] compete against other projects that outrank them.”

The SFP model allows the NRCS to work directly with producers to determine local needs and dedicate funding to address them. That way, said NRCS-Utah State Conservationist Emily Fife, conservation can fit the local context better—both for ranching communities like Rich County and for the wildlife habitat they support.

“Locally led conservation is at the heart of the Strategic Funding Pool model,” Fife said. “It enables NRCS to work with our local communities to determine the current state of our natural resources, the outcomes we want to achieve, and the steps needed to get there. Utah’s diverse landscape and resource needs require strategic funding and focused efforts to ensure success.”

To determine the areas to prioritize for funding, the SFP used recent research on sandhill cranes and the wetland benefits of flood-irrigated grass hay, as well as an app called the Wetland Evaluation Tool that uses spatial data on surface water to track wetland resiliency over time.