Q&A

Q&A with Lead Author Patrick Donnelly

In a paper published in the journal Ecological Indicators, IWJV and partner scientists take a regional look at a drying trend that is impairing wetland habitat across the West. Lead author and former IWJV Spatial Ecologist Patrick Donnelly breaks down the research, as well as its implications for wetland and migratory bird conservation and management.

Learn more about Patrick and his contributions to wetland science.

Q: Can you describe how you’re using satellite imagery to track what wetlands are doing in the West? How is this method helpful for determining changes as opposed to traditional mapping methods?

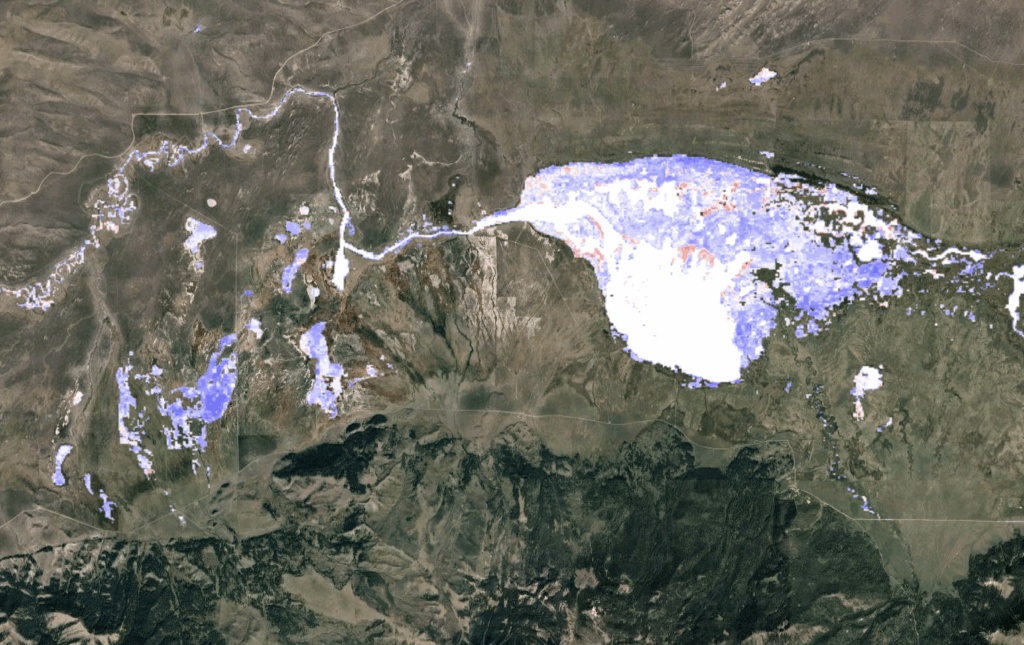

A: Satellites are continuously taking pictures of the surface of the Earth, going back to the mid-eighties. As a result, we have this record of land surface change over time. Through the modeling process, we’re going through that imagery, extracting those bits that are wetlands and then actually delineating surface water extent every single month. That allows us to see how wetlands are changing, not only through annual cycles, but within these monthly periods, or over the course of that long history [since satellites started capturing imagery of the Earth].

This modeling captures the time and space of wetland change. Sometimes it’s difficult to measure because wetlands are so dynamic. If you don’t have a really tight record of what’s happening, it’s hard to measure changes.

And this is really different from how wetlands have been measured, or I guess you’d say inventoried in the past. The National Wetland Inventory (NWI) has traditionally gone in and just delineated wetland footprints, or where wetlands occur on the landscape. It doesn’t really look at how wetlands function ecologically or how water changes the hydroperiod—the duration of flooding. That duration of flooding or wetland inundation is key to all these ecological processes that are linked back to species’ use of these systems, how productive wetlands are, and how useful they are. Our work doesn’t just map where the wetlands are, but how they function ecologically through time and space.

Q: Why is this new way of looking at wetland change particularly important in more arid environments like the Western U.S.?

A: What’s really important about it is that we’re actually monitoring ecological change and function over time, which gives us so much more insight than just whether the wetland is there or gone. What this tells us is if you have a wetland that’s still there, but it’s now dry consistently through time, it’s not functioning anymore. So while it’s still on the landscape, it might as well be gone for those wetland-dependent species that are out there.

I will add what we found in the arid West was that inundated or flooded wetlands make up on average, only about 0.3 percent of the landscape’s footprint. So there’s a very small proportion of wetlands out there. If you look at the wetland inventories they’ve taken where they map the actual footprint of the wetland, those are thought to occupy between three and five percent of the landscape. So it’s a much larger area when you talk about the footprint where water could be versus the footprint where we determined water actually is. And so because it’s such a rare commodity and structure with so much biodiversity, because wetlands are a limited resource in arid systems, if that footprint changes it can have massive rippling effects across entire ecosystems.

Q: Why does tracking wetlands matter for migratory bird conservation?

A: When we think about water birds like waterfowl, or sandhill cranes or wading birds like white-faced ibis, they migrate over these very large geographies that might start in Alaska and go to Central or South America, and multiple places in between. The timing of their movements is often structured around these very rare wetland types found across the landscape. Understanding changes to that availability and how they shift in time and space can have rippling effects because migratory waterbirds have life dependencies that are tied to these wetland systems, whether it’s breeding or migration, where birds need to be in a certain place to gain those energetic resources specific to their seasonal need.

Then we have what we call cross-seasonal effects, where the conditions in one landscape might be very dry, so the birds can’t find water resources. Their body condition might change to the point that when they reach the breeding ground two months later, they’re not able to actually reproduce. This creates what we call a source-sink situation, where conditions in one part of the flyway that cause deficits in wetland condition affect the life history events of birds in other parts of the flyway. Understanding and tracking wetlands on these large scales becomes really important so we can be more targeted in how we deliver conservation to offset some of those potential impacts to migratory birds.

Q: Why is it important to conserve the ecological processes of wetlands through management? How can land managers use this data?

A: There’s a link between this continuously changing landscape that’s drying over time because of increased temperatures and changing water use policy and the management of public lands. Land managers have an important role to play in offsetting some of those impacts. Knowing how to manage those public lands wetlands requires understanding what’s happening in all the landscapes around you, including on private land.

Using this data can help land managers understand not only what’s happening within our public land systems but on the surrounding landscape. This is important in informing conservation planning to offset the ecological change that affects priority species across the region.

Q: How do natural wetlands complement managed wetlands? Can you give an example of where we see this occurring in the West?

A: Typically, we put public managed wetlands or wildlife refuges inside places that are already important to water birds or wetland dependent species, and they have high density wetland systems that are there. I think about places in the Southern Oregon Northeastern California region, like the Harney Basin, where we have Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, which secures wetland systems surrounded by these terminal lakes like Malheur Lake. Those systems are adjacent to private lands upstream in the Silvies River floodplain and the Donner und Blitzen River floodplain that use flood-irrigated agriculture like grass hay production to support private lands ranching operations.

Flood-irrigated grass hay practices can have ecological benefits like groundwater recharge. They also create wetlands through the irrigation process. Now while these systems are typically ephemeral, temporary wetland systems, they complement these adjacent public lands by providing additional resources for birds during parts of the year where the systems and those irrigation resources are available. In high-density wetland landscapes, we usually see a composition of public and private lands that in many ways can work together to provide wetland resources and ecosystem services that complement one another.

This is not always the case, though—there are times when groundwater pumping for irrigation have dewatered wetland systems. In some regions of the West, sprinkler irrigation has actually lowered water tables through groundwater pumping actions and reduced the wetland footprint in those systems. So it’s not always a win-win. There’s always reactions that can be non-complimentary to wetland function as well.

Q: This study indicates that agricultural wetlands play a huge role in providing wetland habitat across the region. What do these places look like and how are they offsetting shrinking natural wetlands?

A: There are places like the Wyoming Basin or the Upper Green River that have these enormous wetland footprints. The timing of those wetland systems is tied to snowpack. Those rivers pull water down off the mountain and flood-irrigated agriculture helps spread it across these landscapes, typically toward midsummer. There’s a certain suite of species that are tied to that, like breeding sandhill cranes, which are really well adapted to that land use practice.

These systems are often really ephemeral as well. And so when we look across the West, there’s a select suite of species that really benefit from that. Sandhill cranes are one, cold water fisheries and native trout are another. When you spread water across a floodplain, mimicking natural processes that would occur when spring rivers would flood over banks and spread water across the floodplain, that water seeps into that upper horizon of the soil. As groundwater slowly makes its way back to the channel and is kind of reinfused into the channel by midsummer, it maintains stream flows and water temperatures, keeping it cool in late summer for species like cutthroat trout that utilize that habitat and need it. So that type of role agriculture plays for wetlands and habitat is critical across the West.

Q: If you could provide one takeaway for western wetland management as a result of this study, what would it be?

A: It’s important to understand that these systems are dynamic and they’re changing quickly, and that to really be adaptive and meaningful in how we deliver conservation, we have to be very aware of what those changes are. We also need to understand how we can relate those changes across public and private lands to find solutions that create efficiency in the way we deliver conservation.

Because public lands have increasingly less water, they may have to manage their wetlands differently to offset the changes we see on broader scales. Private lands can play a role in that. Can we do more to conserve and hold up with some assurances that private lands wetland conservation will occur into the future? Can it be relied upon to create more flexibility on adjacent public lands? We need some assurances that private land conservation efforts will also be there for some period of time. There’s a balance of conserving agriculture on private land and then leveraging that so that public lands can adapt their systems based upon what’s happening around them. This results in a more efficient use of a limited resource to benefit species, ecosystem services, and wetlands into the future.

Looking for more IWJV wetland science? Learn more about this study, similar research, and how satellite data is informing wetland management across the West here.