Explore this feature story about the Two Watersheds – Three Rivers – Two States Cohesive Strategy Partnership (2-3-2 Partnership), a collaborative effort between many groups invested in the ecological and social health of a five-million-acre landscape.

Story and photos by Hannah Nikonow, IWJV Communications and Marketing Coordinator

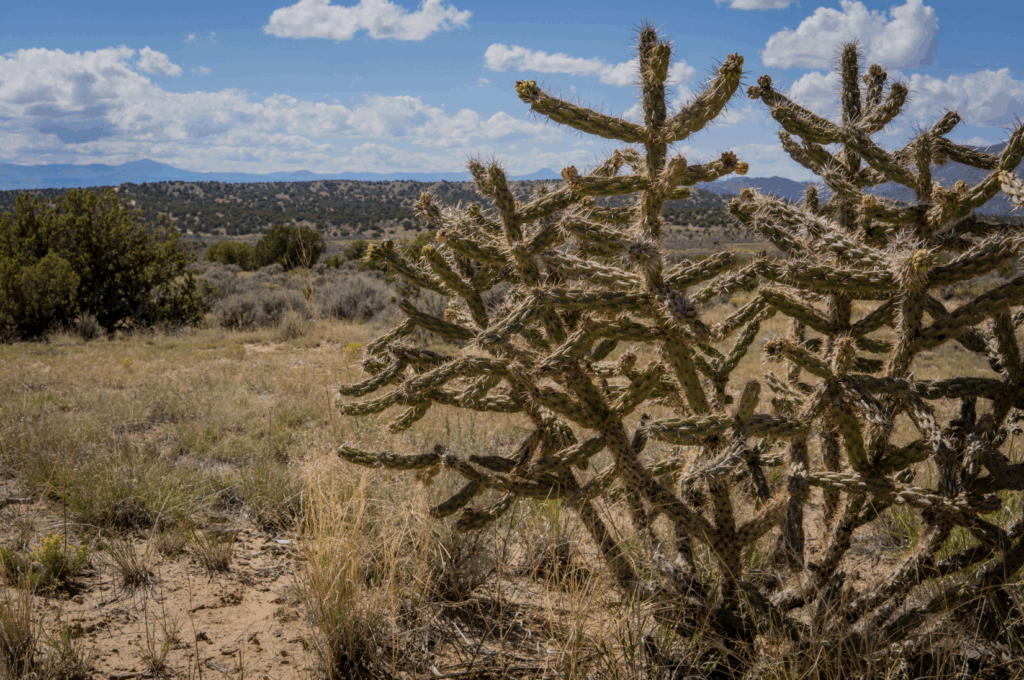

There’s a place that spans three rivers and the Colorado-New Mexico stateline where a little water and some tacos go a long way. There, people have come together to get hard natural resource management work done, but it was never a forced relationship in response to disaster or regulation. In this place of dry forests, high mountains, and vast deserts, a collaborative group is pushing towards a shared vision of ecological and economic resilience with critical social implications.

In 2016, concerns about forest health and water quality brought people to a common table. What resulted is called the Two Watersheds – Three Rivers – Two States Cohesive Strategy Partnership, better known as the 2-3-2 Partnership. This partnership is a network of conservation stewards, including local, state, and federal agencies, Tribes, non-profits, and community organizations. By working across land types and ownerships, the 2-3-2’s collaborative model amplifies the impact of individual projects, creating a unified effort for landscape restoration and management.

“The 2-3-2 is unique in that it crosses all sorts of human-created lines, like the Continental Divide and state lines, as well as social and cultural divides,” said Lily Bruce, Southwest Project Manager with Forest Stewards Guild. “To meet your targets of success on the ground, it takes eating a lot of tacos together. It takes an incredible amount of work to get social acceptance of land management, but the nature of this cross-boundary effort facilitates conservation at the scale and pace we need.”

The 2-3-2 Partnership encompasses the San Juan, Rio Grande, and Rio Chama watersheds, operating with a multifaceted vision: to reestablish natural fire regimes, protect and improve water resources, enhance wildlife habitats, and support the cultural and economic well-being of local communities. The 2-3-2 is also deliberately decentralized in its governance. There is no single leading organization or hierarchy of decision-making.

In September 2025, the 2-3-2 Partnership met for its tri-annual meeting. This event, held in Antonito, Colorado, focused on storytelling and communication. In a tour of the Notch Project in Conejos Canyon, the group shared about successes, challenges, and what we can all learn from those experiences to improve and expand how we communicate about our conservation work.

For example, in a 2-3-2 meeting or project, rural producers collaborate with downstream water utilities, regional U.S. Forest Service staff, state agencies, and youth conservation corps crew managers. Together, they design forestry work that protects water infrastructure from severe fire and post-fire flooding, and pay local youth to make it happen as well as monitor the lasting impact. This all-hands-pulling-together approach is what makes prescribed burning, forest thinning and logging, stream restoration, and other such projects that cross property and jurisdictional boundaries possible and effective.

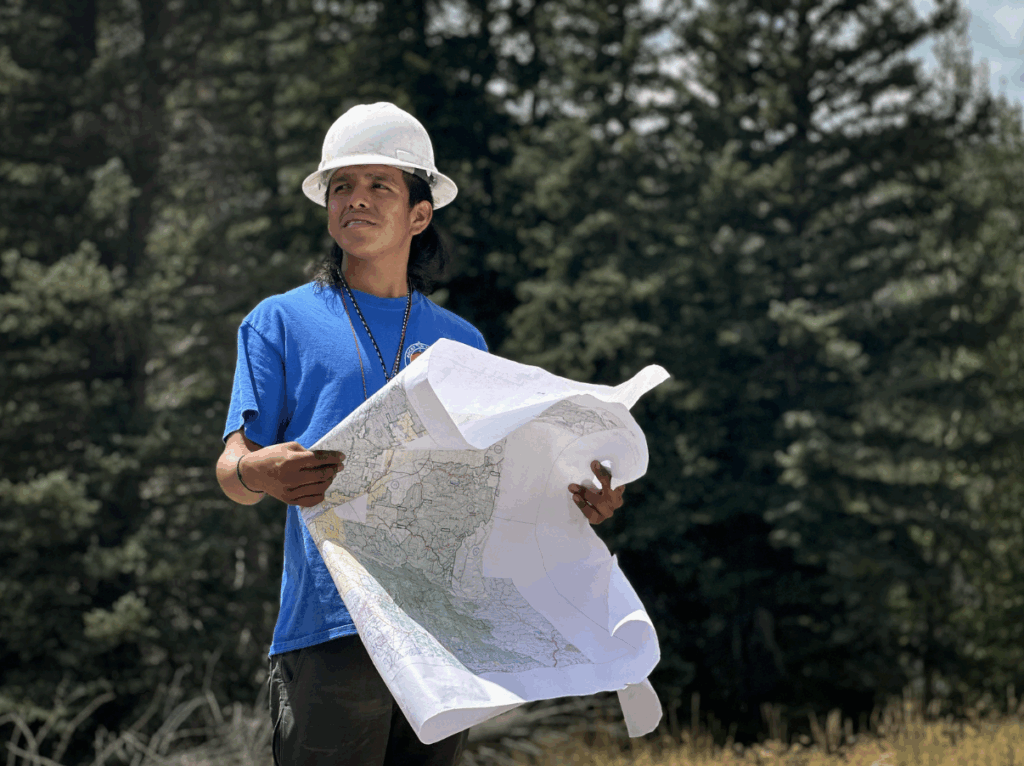

Left: To reduce the likelihood of wildfires, pre-plan for post-fire impacts, and develop a culture of shared responsibility, the Forest Service partnered with nearby communities and organizations to secure CFLRP funding. Here, Rocky Mountain Youth Corp Seed Crew Member Jude Ansala, with the Zia Pueblo identifies trees with superior seeds used to reforest areas impacted by fire. Photo courtesy of: Preston Keres, USDA Forest Service.

Right: In the Rio Chama CFLRP, one tool for building resilient forests is prescribed fire. As part of the CFLRP’s goals to train future forestry professionals, Forest Stewards Youth Corp Crew Members from Jemez Pueblo supported the North Joaquin Prescribed Fire in 2024. Photo courtesy of: Forest Stewards Guild

Managing Fire and Water for Community Health

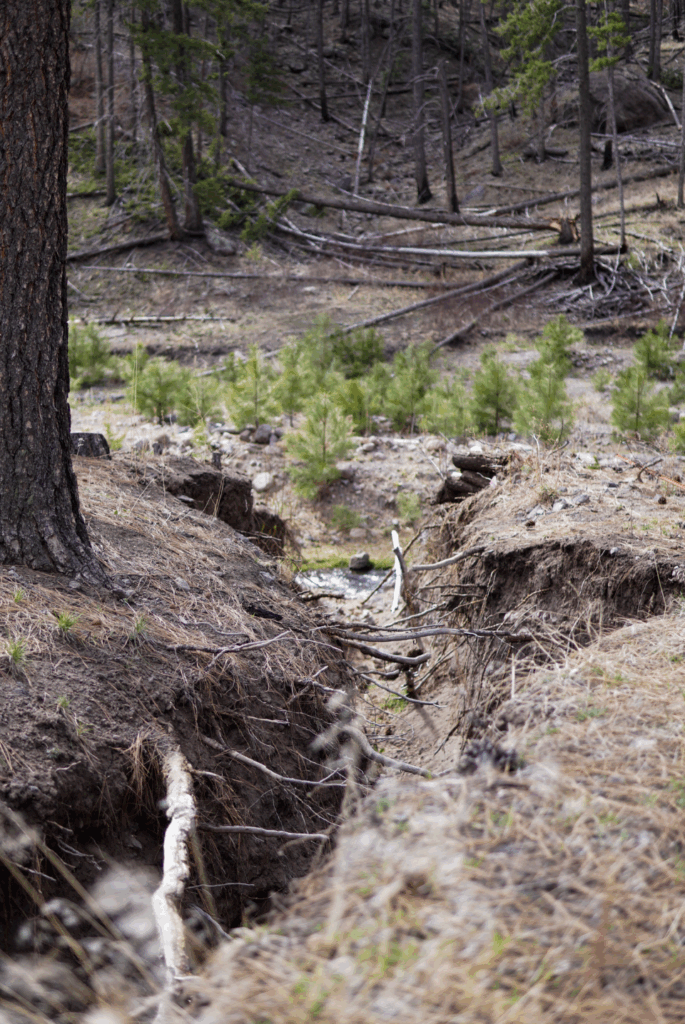

The 2-3-2 Partnership’s goal of restoring fire-adapted landscapes is one of the most difficult and daunting, yet it’s connected to the preservation of the most precious resource in the American West: water. For the past 100 years, people have been remarkably effective at suppressing forest fires, allowing the understory to build up with excessive growth. Historically, wildfires occurred frequently in these forests, at lower severity and smaller scales. Today’s fires are hotter and larger, killing many trees that otherwise would have survived. When fire does spark, that continuous fuel source burns hot and expansively. This removes the trees that would provide soil stabilization and slow the water moving down slopes, hardens the soil, and burns out riparian areas. Another hazard develops after fires are put out: when large rain events occur, which are common in the southwest, the runoff blows out creeks, causing erosion, sending silt downstream into rivers and reservoirs.

One community severely impacted by multiple large fire and flood events is the Santa Clara Pueblo. Located in northern New Mexico, the current-day reservation extends from the top of the eastern Jemez Mountains to the floodplains of the Rio Grande River. Daniel Denipah is the Director of Forestry for Santa Clara and he said they have had to shut down access to important canyons and creeks that have become hazardous due to the road damage caused by fires and floods. He shared that the tribal council members are worried because there are young people who haven’t been able to experience these places and are losing connection to them.

“That’s why we are including the kids to get their hands involved in restoration projects like tree planting,” Denipah said. “We want them to be a part of putting back the native species into that system.”

Denipah and his colleagues have been involved since the founding of the 2-3-2 Partnership because he knows how much each partner involved can be impacted by the land management work that others do.

“Our people since time immemorial have lived in the lands that are now considered outside our pueblo and we have many cultural sites elsewhere,” he said. “We want to see places protected beyond our community because it is important that the land’s health extends well past our boundaries. These places are all a part of our histories, our trade routes, our stories, our language, and our songs. It’s important to our way of life, now and before.”

“The tribe understands that forest health work is part of a much bigger picture. People belong to the earth more than they own it. It helps identify who we are as Santa Clara people and our place in the world. It’s our culture and our way of thinking. Forests are part of our prayers.” – Daniel Denipah, Director of Forestry, Santa Clara Pueblo

Planning and Paying for Landscape-scale Resilience

Weaving together management strategies, working across jurisdictional land and organizational boundaries and restrictions, and ultimately implementing a project requires an incredible amount of care to get right. Joe Carrillo with the New Mexico Energy, Minerals, and Natural Resources Department said that this type of work can be a test of patience due to the time it takes from applying for funding to completing the project planning to the moment when implementation begins.

“Completing a project once started is usually the easy part,” Carrillo said. “But the planning is the most exciting opportunity because you get to formulate and develop ideas based on science, economics, social importance, safety, and the opportunity to create a project that you hope will provide the greatest benefit to meet your objectives.”

This nuanced planning, with dedicated partners involved through the whole process, led to a pivotal moment in the partnership’s development, as members focused on shared resources and opportunities to enhance rural economic development through forest management. This resulted in the Rio Chama Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP) proposal, which was funded in 2022. This has turned the 2-3-2’s ideas into action, leveraging critical funding to attract nearly $40 million in additional resources, extending restoration efforts beyond federal lands.

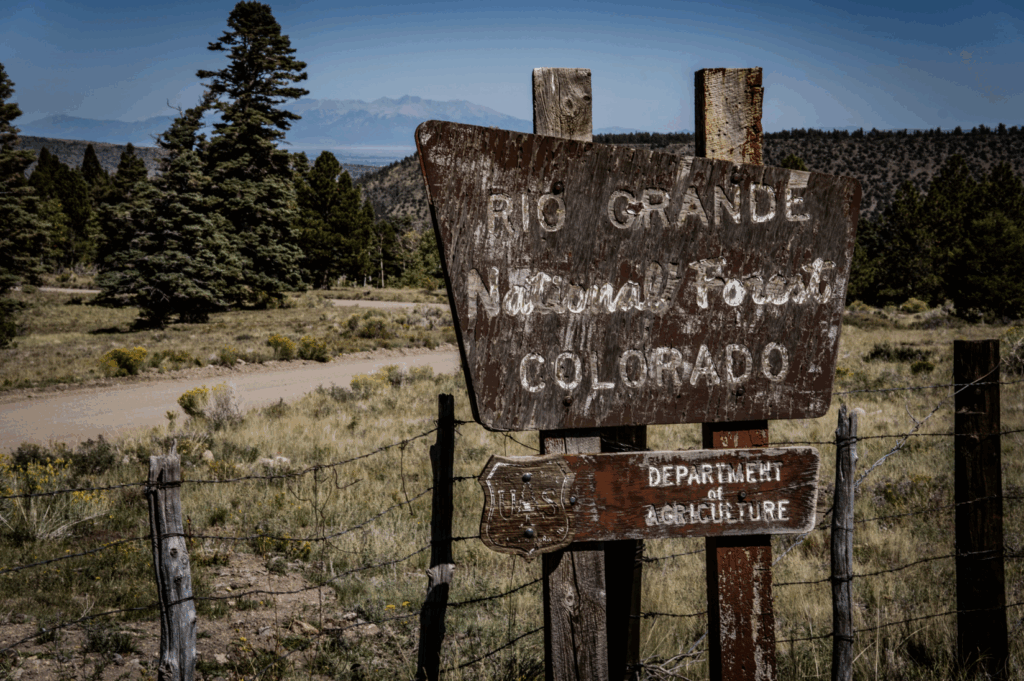

William Foster with the New Mexico Energy, Minerals, and Natural Resources Department, Cody Dems with the Forest Stewards Guild, and Andrea Jones with the U.S. Forest Service are in the field traveling the Colorado-New Mexico state line on the Rio Grande National Forest to see multiple years of timber management funded by the CFLRP. At this project site, numerous conifer species are being removed to promote the health of aspen stands. Elk and mule deer as well as numerous forest grouse, woodpecker, and owl species, thrive in these treated project areas alongside cattle in this working landscape.

The Value in Details

Even though the subtleties of how innovative and dynamic partnerships work may seem a bit convoluted, they are everything to the people working to conserve these beautiful landscapes. Governance strategies, water quality and quantity, and the cost of forest management all take an incredible group of people to make progress. Neighbors must lean on one another in much of the world, and in the 2-3-2 region, this is no different. For their mission to be accomplished, everyone must be a leader and a supporter. Everyone must share their many types of knowledge. And everyone partakes in the tacos.

The Notch Project, supported by the CFLRP, is going to thin this 2,000-acre area to decrease forest pest presence and maintain healthy aspen and douglas fir. This work is critical to reduce the region’s risk of catastrophic fire that would threaten the area’s water supply and downstream homes.