Restoring the Ravine with the Environmental Quality Incentives Program

EQIP makes applying low-tech process-based restoration practices like beaver dam analogs an approachable solution for Utah landowners.

Kent Baker (left), Justin Deakin, and Nick Reithel inspect one of the beaver dam analog (BDA) structures installed on his land to help retain water and restore dryland pasture.

It’s a hot July mid-afternoon, and Kent Baker is down in the weeds. Some of them are noxious, and those he’s working to eradicate, but many are native—grasses and sedges, tiny saplings of shrubs like chokecherry and fernbush. The ravine is exploding with vegetation—a green ribbon from where it emerges out of the national forest and cuts through golden foothills to reach the floor of Utah’s Cache Valley. Baker is waist-high in the middle, straddling a foot-wide trickle of water.

It’s unusual for the ravine to have surface water in the middle of summer, but Baker is pleased to see it. If there’s enough flow for water to appear on the surface, there’s enough water to infiltrate deep into the ground here and feed a spring that provides the bulk of the irrigation water for his farm operation.

A BDA structure on Kent Baker’s Cache County, Utah property one year after installation.

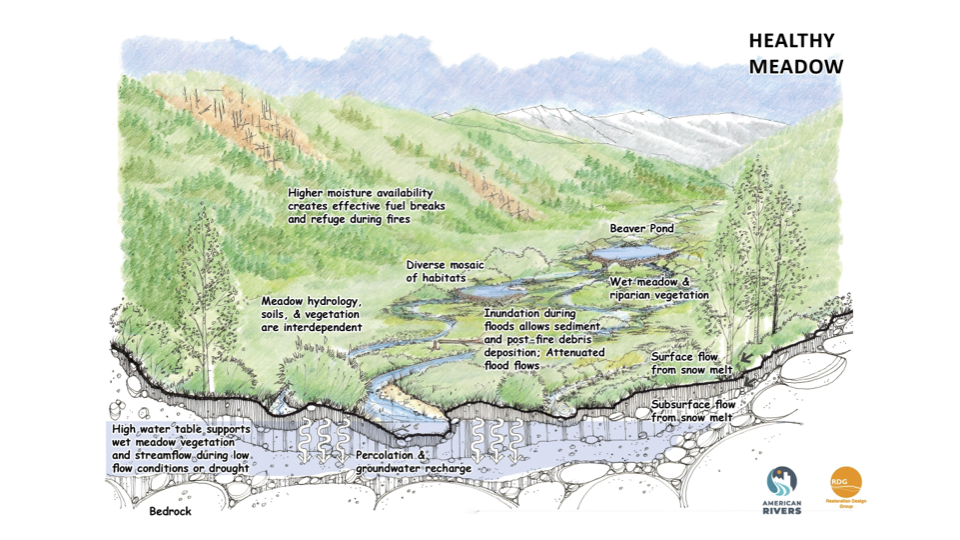

The burbling sound of water is also an indicator that the beaver dam analogs Baker installed two years ago are working. These structures, commonly referred to as BDAs, mimic the dams that beavers build to slow water down and spread it across the floodplain. There are 52 of these structures in this ravine, starting at the top of Baker’s property and extending down nearly to the irrigation pond filled by the aforementioned spring. The BDAs were installed after Baker worked with the Utah office of the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to apply Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) funding to help restore this site.

“NRCS suggested it, and it made sense with my idea of trying to fix the flow of water here so that maybe it would help the spring,” Baker said.

Restoring the water flow through this ravine is key to Baker’s larger goal of restoring his 160-acre property in Utah’s Cache Valley. The ravine cuts sharply through the upper 80 acres of his property that were once used for dryland wheat farming. Baker wants to restore dryland pasture to this hillside and eventually use it for regenerative livestock grazing. Boosting water infiltration into the soil through here will help him irrigate his lower 60 acres (currently in no-till wheat production) and revitalize these dry upper hills.

The BDAs also help with a more community-focused goal: flood control. By spreading water across the landscape, BDAs lessen the strength and speed of high flows and keep water from racing away down the watershed. Although running water in the ravine has been historically uncommon, what’s not unusual is for the occasional odd event—say a microburst or a big runoff year—to fill this ravine with water.

“When this floods, it destroys houses,” Baker said, pointing at the houses downhill, including his own.

The BDAs were put to the test the first year after they were installed: a heavy winter snowfall led to a high runoff event in the spring. The event damaged several structures (which are not intended to be permanent), but many held—and collected important sediment behind them. Temporarily trapping sediment is an essential step in seeing the benefits of BDAs, filling in incised channels, helping to raise water levels behind dams and allowing that water to move outwards towards the floodplain. Creating a connected floodplain with complex stream structure is an important function of BDAs. Complex stream structures tend to support more riparian vegetation and wildlife habitat. When streams lose that structure, those benefits go out the window.

Credit: American Rivers

“A lot of streams are structurally starved,” said Stephen Bennett, a founder of riverscape restoration firm Anabranch Solutions and the lead on installing Baker’s BDAs. “Either beaver dams or living and dead woody vegetation is no longer there. Those obstructions to water flow pond water, and when you pond water, it forces surface water down into the groundwater. Without structure from dams or vegetation, water has more energy and incision occurs—the water erodes into the streambed, causing incision. That disconnects the floodplain from the stream channel, so the surface water drops and so does the groundwater.”

With many BDA projects, the goal is to encourage beavers to return to waterways and take on the work of maintaining stream structure. In other instances, like Baker’s project, the goal is merely to mimic the work that beavers can do, either because the critters are not wanted in an area or because a location isn’t going to support beaver habitat. Then, the maintenance of structures is left up to people.

“This isn’t enough water to interest them—that’s why the analog part of the beaver dam analog makes sense here, because the beaver aren’t going to use this area,” Baker said.

A game camera set up to monitor the project site shows spring runoff about a year post-installation.

Beavers can also be tough on irrigation systems and are not always wanted in streams. Nick Reithel, the Watershed Coordinator for the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food, is working with Baker to help monitor his project. He said that BDAs can be a tough sell on private land because there are many questions about this relatively novel practice.

“The hard part of the conversation is always, ‘Are you going to bring beavers back? Is this going to flood my land?’” Reithel said. “Those are some questions that landowners can find challenging.”

But an NRCS program like EQIP can make approaching a tool like BDAs easier. By providing an avenue for landowners to install low-tech structures like BDAs, Bennett said, EQIP is helping increase the pace and scale of riparian restoration on private land.

“Recognition by the NRCS allows BDAs to be installed on many private properties,” he said. “The NRCS is so intimately connected with ranchers and farmers that it will increase the amount of this work being done on private ground.”

Vegetation obscures the BDAs in mid-summer 2024—vegetation that will continue to slow the water down and keep the ravine from becoming a firehose during flooding events, which is the ultimate goal for Baker’s project.

That pace and scale is essential when it comes to tools like BDAs, said Gabe Murray, who held Reithel’s position previously and, in that role, encouraged Baker to look at BDAs as a restoration tool. Murray connected him with EQIP funding (Murray now is the Executive Director for the Bear River Land Conservancy). One low-tech restoration project isn’t going to change much beyond the stretch of stream it’s installed on; however, many such projects within an area can have watershed-scale impacts for both wildlife and communities.

“BDAs are creating different microhabitats throughout the watershed that may have been lost,” he said. “Any single project isn’t going to move the needle, but doing multiple projects throughout a watershed, those impacts add up.”

The fact that the BDAs mimic a natural process is a selling point for Baker. A career as a landscape architect taught him that working with nature, rather than against it, leads to better results in the long run.

“If you work with nature, there will be more positive things that happen,” he said. “At least I hope so—that’s kind of my philosophy.”