Irrigation intensification impacts sustainability of streamflow in the Western United States

A Q&A with David Ketchum, USGS remote sensing and geospatial information specialist

Lead author of Irrigation intensification impacts sustainability of streamflow in the Western United States

David Ketchum’s research with the University of Montana looks into the relationship between irrigation intensification and in-stream flows in watersheds across the western United States. As climate-change-induced drought impacts water availability for habitat and agriculture in the region, this science identifies where modern irrigation systems benefit basin water supply, and where less efficient systems contribute to return flows and relieve ecological stress.

Q: What does this science say about the way irrigation practices are changing in different landscapes?

A: Our analysis shows that irrigation is intensifying around the Western US. This is a product of a notable increase in both irrigated areas and a greater amount of water used by crops. In our paper, we link these changes quantitatively in some places to the conversion of irrigated systems from gravity-fed irrigation water application (such as flood irrigation) to pressurized systems (such as center pivots).

We show in our paper that as irrigation water use increases, the response in terms of stream flow changes is nuanced and likely related to the unique characteristics of each river basin, the irrigation systems and management practices in place, and the climate of the region. Our work indicates that irrigation systems sometimes thought of as inefficient are likely returning water to the basin from which it was diverted, making it available for later use by water users and available to ecological systems.

Q: What research is needed to better paint the picture of water use and return flows in the West?

A: Our data shows irrigation statistics that demonstrate the amount of water diverted. The area covered by irrigation-equipped agriculture may be further improved by incorporating estimates of irrigation water use through crop evapotranspiration, or what we often call ‘crop consumption.’ Although we can capture in broad terms the changes in our irrigated landscape through water use surveys, remote sensing-based estimates of crop water use add a lot of value to our understanding of total water lost to the atmosphere through irrigated agriculture in our watersheds.

evapotranspiration, or what we often call ‘crop consumption.’ Although we can capture in broad terms the changes in our irrigated landscape through water use surveys, remote sensing-based estimates of crop water use add a lot of value to our understanding of total water lost to the atmosphere through irrigated agriculture in our watersheds.

Our approach is empirical; we can show there are relationships between climate, irrigation water use, and streamflow at the basin scale. However, our approach cannot quantify the precise amounts of return flow and track unused irrigation water as it moves through each system at the local scale. For this, we might need to develop watershed modeling approaches that explicitly track water as it moves through each system. This physically-based modeling approach would enable us to use the history of stream gaging, meteorological records, and remote sensing of irrigation water use to account for the past and predict how our watersheds might behave in the future under different management and climate scenarios.

Q: What does this science mean for western water management?

A: The main takeaway for management is that our natural and managed hydrological systems are connected and that modern sources of data (like remote sensing estimates of irrigation water use) provide us with information that we may be able to use to our management advantage.

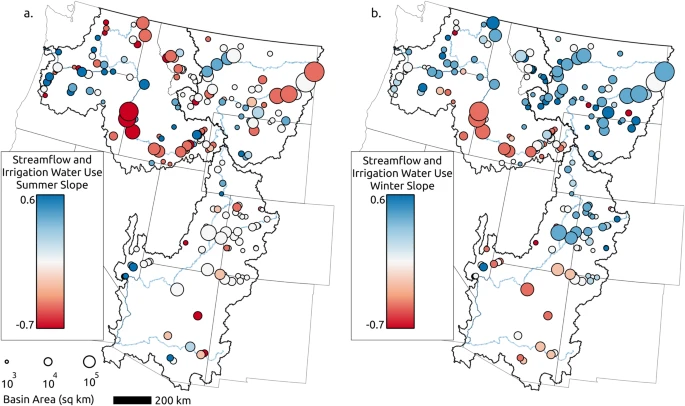

Maps show the relationship between climate-normalized streamflow and water use for irrigation in a) summer (May through October) and b) winter (November through March). Blue represents a greater proportion of water in streams and less use for irrigation water, and red shows lower streamflow and higher irrigation water use.

Q: What technology or data-gathering techniques are needed to help irrigators make informed decisions at smaller scales? Is there technology that exists that should be more widely used/accessible?

A: Watershed-scale modeling of the hydrological systems coupled with local-scale meteorological, groundwater, and tributary streamflow observations would allow irrigators to keep up-to-date on water availability and use. Easy-access and straightforward tools such as the drought dashboard and Mesonet dashboard, provided by the Montana Climate Office, allow users to quickly access important and up-to-date water resources and weather information. My hope is that water managers and irrigators see these new tools as usable and that they consider making use of such information in their work (such as Jenna Dohman’s work in southwest Montana).

Q: How can irrigators and other water managers work together using this data?

A: This and other timely data that provide information about irrigation water use might be helpful to irrigators and water managers who want to work together to maximize the use they get from available water sources while keeping in mind the potential impacts of changes to irrigation management.